American Strategy analysts knew that USSR dreamt of access to the Indian Ocean. They had to be resisted. The strategically located Chagos Archipelago would emerge to become a priged location for American Military operation. One has to dissect the state of mind of each of the main protagonists in this real life drama: (a) the Americans (b) the British (c) Mauritian Colonial Leaders. The American set to outface the Russians wanted to become the leading military power in the Indian Ocean, if not on planet earth. Britain had to face the reality of the sun setting on its empire and had to desperately solve domestic political problems and a sterling crisis. Mauritian colonial leaders were aspiring legatees of the British in a possibly decolonized or integrated-to-UK Mauritius.

Declassified papers reveal that there were preliminary UK-US negotiations on the use of the Chagos during cold war years from 1957 to 1965. In 1957 US Admiral Jerault Wright made an explorateurs visit to Diego Garcia followed by another in 1961 by Admiral Jack Graham. From 25th to 27th February 1965 highly confidential discussions took place in London between the USA Department of State and the British Ministry of Defense. The Americans came with an unusual, rather bizarre, proposal. They wanted the Chagos Archipelage to be detached from Mauritius and Mauritius to become independent. They did not want to be party to the detachment process nor to the constitutional process leading to Mauritius independence. Records of the meeting reads as follows: « From the military point of view, Diego Garcia and the Chagos Archipelago should be detached from Mauritius now. It would be advantageous if they were to come directly under United Kingdom administration. The United State delegation is very anxious that the settlement of the constitutional issue of Mauritius Independence should be pursued as quickly as possible ». On 14 June 1965 in a memorandum bearing a security cover marked « secret » US Secretary of Defense Robert S. Mc Namara to Secretary of the Air Force Eugene Zucker he expressed a secret commitment by the Pentagon to contribute up to US $14 million to « the British costs of detaching certain islands in the Indian Ocean from their present administrative authorities ».

The « detail »!

In UK itself information relating to the UK-US discussions was classified with restricted circulation confined to the British Prime Minister (Harold Wilson) and his Defense Secretary, top chiefs of staff of the UK Forces (Army, Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force), Sir Burke Trend Secretary to the British Cabinet, Permanent Secretaries of the Ministries of Defense, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and to Sir Hilary Poynton of the Colonial Office. The Colonial Secretary Anthony Greenwood it appears was not in the picture, as the tenor of a minute dated it June 1965 written by Sir Burke Trend (Cabinet Secretary)- to the Prime Minister Harold Wilson suggests. Extract of Sir Burke’s minute to the PM reads « … the Colonial Secretary is silent on this point; nor does he say whether he has consulted the Governor… How are the proposals for constitutional advance related to the proposals to detach certain of the dependencies of Mauritius as part of our plan for organizing a chain of island bases in Indian Ocean… » Greenwood acted on two clear instructions emanating from the Cabinet Office : (a) Mauritius would become independent, integration was ruled out (b) Minority rights within majority rule would be guaranteed with full equal citizenship rights in the Constitution. The priority for the British Government was, first and foremost, the detachment of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius and the Western islands of Aldabra Farquhar and Desroches from Seychelles (aftewords returned to them in 1977) and the setting up of one of the last born colonies of our times, the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). A novel form of imperial colonization of the Indian Ocean in the age of decolonization! And Britain proceeded, with dexterity and gusto,to, in getting the consent apparent or implied, of the Mauritian Colonial political class led by SSR.

Having carefully planned the excision of Chagos by February 1965, the British Government made preparation to tackle the Mauritian delegation seven months later in September 1965 on a three-front assault (a) The Mauritius Constitutional Conference will be presided by Greenwood who expressed his desire on Monday 20 Sept 1965 « to keep the discussion of the proposal to establish defence facilities in Maurtian dependences (Chagos) seperate from the constitutional confrence and his double role as spokesman of HMG interest in the matter and as custodian within the British Government of th interest of Mauritius » (b) Sir Hilary Poynton will preside in his office away from Lancaster House, the discussion in the « UK -Mauritius Defence Agreement » (c) Prime Minister Wilson will placate SSR into submission on the excision of Chagos at his office in Downing Street in 23 Sept 1965. The Steering brief dated 22 sept 1965 of his advisor J.O. Wright is elognent « SSR is coming to see you tomorrow at 10.00. The object is to frighten him with hope that he might get independence. Fright lest he might not unless he is sensible about the detachment of the Chagos… call him Sir Seewoosagur or Premier his official titles. He likes to be called Prime Minister… Getting old. Realise he must get independence soon or it will be top late for his personal career. In a minute that J.O. Wright wrote (he was the only official present at the Wilson/SSR meeting) says « SSR said he was convinced that the question of Diego Garcia was a matter of detail, there was no difficulty in principle » 47 years after, today, Diego Garcia, « the detail » has grown into the biggest problem of Mauritius territorial claim;

It can be argued that Mauritius independence and the immediate 14 year old post-independence saga until 1982 are, by and large, a repetitious nationalist hagiography centred on Sir Seewoosagar Ramgoolam. We will next look at how the liberator became oppressor and lost power in 1982.

The Independence decides by Britain !

Tuesday 12 March 1968 was perhaps the longest and the most memorable day for the then 67 years-old Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam (SSR). Mauritius became independent on that day. After a week of torrential rains, it was unexpectedly calm and sunny. SSR had already assumed the title of ‘Prime Minister’ since 22 november 1967 by arrangement when the date of independence was agreed, at British behest, because of his dilly-dallying. It was the day of liberaiton from colonial yoke. But an independence decided by Britain after the excision of the Chagos Archipelago.

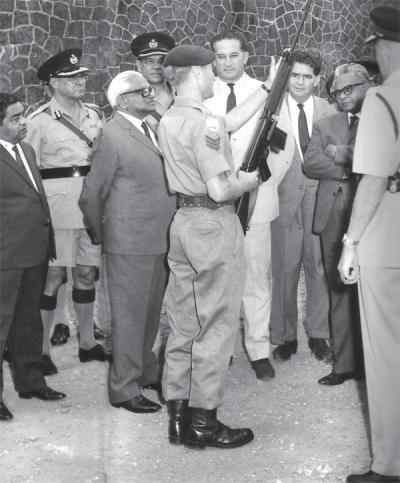

Mauritius had barely recovered from a bitter communal conflict between creoles and muslims and a battalion of 150 British soldiers from the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI) was until lately patrolling the streets of Port-Louis to keep peace. In the harbour of Port-Louis two Royal Navy Ships, HMS Tartar and HMS Carryport, joined by the Indian Navy Ship Delhi and the United States Ship F. J. Ellison and a French destroyer symbolically kept watch while their crew members took part in the celebration. Half of the Mauritian people sulked at home because they had expected integration with the U.K. The other half rejoiced and so joined the celebration because they got ‘Azadi’ (independence). SSR accompanied by Lady Sushil, daughter Sunita and son Navin Chandra arrived around ten at the Venue, Champ de Mars, in a post car bearing registration ‘IND1’. The Governor Sir John Shaw Rennie, dressed in traditional attire and a plumed hat accompanied by Lady Ronnie, and escorted by Assistant Commissioner of Police, Paul Perrier, arrived just before 11 a.m. After a military parade accompanied by music of the Police Orchestra, Lieutenant D.E. Wenn of the Royal Navy lowers down the « Union Jack » to the sound of « God Save the Queen ». At exactly 12 noon Inspector Palmyre of the SMF raises the Mauritian quadricolor accompanied by the national hymn. The crowd acclaims frenetically. Despite all the odds, the raising of the quadricolor, it must be said, created the semblance of a talismanic moment in Mauritian public life. On the eve, on Monday evening, at Queen Elizabeth College, Rose-Hill, SSR presided over a state banquet in honour of foreign delegates and Mauritian V.I.P’s. Champagne flowed.

Greenwood tendered SSR the best wishes of Britain and saluted him as « architect of this young nation », He, SSR, is today called « Father of the Nation », perhaps rightly so to most Mauritians. In the sanctum sanctorum of our political deities, SSR has certainly carved himself a prime place. One can however argue, in the same vein and with the same verve, that independence and the immediate 14-years-old post independence saga are, by and large a repetitions nationalist hagiography centred on SSR. Indeed documentary and archival evidence of his picaresque personal and xenophobic political adventures are at odds with this hagiographical portrait. Let us go back almost three decades earlier in our history: 1937.

The « Agitators » and the « collaborators »

On an inauspicious date Friday 13 August 1937 there was at Gujadhurs’ Union Flacq Sugar Estate, a confrontation between, on the one side, labourers and small planters, and on the other side, police and estate personnel. The encounter shows the desperation of an exploited and politically ignored working class and its attempt to redress its grievances. It also shows the hautiness of sugar millers and the determination of the colonial regime to maintain law and order at all cost. On that day three casual labourers were shot dead and several others were seriously injured. The events mark a turning point in the socio-economic and political history of Mauritius. When news of the riot and death reached the Colonial Ofice (Co), officers there reacted with disbelief and show. A. Bevir, a Senior official, minuted on 17 August 1937 in a classified file « the estate owner in Mauritius is reactionary and short-sighted (which indeed we have suspected) and the conditions of labour of the sugar estate leave much to be desired ». Another official, P. Rogers minuted on 24 August 1937. « It may be decided that a definite set of policy should be taken in Mauritius such as a revision of the Constitution on more liberal lines, a more definite labour policy. This might most usefully be done in discussion with Sir Bede Clifford in connection with a petition which has recently been received from Dr Curé and which is now under consideration ».

Two groups of colonial politicians, diametrically opposite in their thinking, will position themselves on the political scenario. One which the colonial regime described in a derogatory term as ‘Agitators’, populist-militants with their own ideas of proposed changes. The other group is what revisionist historians by contrast call ‘Collaborators’, moderate western-educated, generally anglophile mostly indians. However both the ‘Agitators’ and ‘collaboraters’ were opposed by a francophile class of journalists, the most extreme being Noel Marrier d’Unienville (NMU). Uttam Bissoondoyal in a rather simplistic approach, analyses post 1937 history in terms of this ‘anglophilia-anglophobia’ dualism in his book ‘Promises to keep’ p.88. The ‘Agitators’ were Anquetil, Rozemont, Pandits Sahadeo and Ramnarain, Dr Curé, who founded the Mauritius Labour Party, and the Bissoondoyal brothers, Basdeo and Sookdeo. The ‘collaborators’ were Dr Seewoosagur Ramgoolam (ostensibly the most anglicized of them all) Vaghjee, Beejadhur and others clearly identifiable. Dr Ramgoolam will be nominated to the Legislature in Nov 1940 by Governor Sir Bede Clifford. In a biographical profile, the successor of Clifford, Governor Sir Donald Mackenzie-Kennedy (better known as DMK) dated 2 August 1948 says on Ramgoolam « has considerable influence amongst the Hindus and of their self-appointed leaders, is the one most likely to obtain control. I have hopes Dr Ramgoolam will become more moderate with increasing responsibility ». DMK’s successor, Governor Sir Hilary Blood, in a note dated 27 Nov 1952 writes « the blameless Liaison Officer content to support fully the policy of the Government… the cooing appraiser of Government measures ». Blood’s successor, Governor Sir Robert Scott writes in a profile in June 1955 « the ablest politician in Council… a gentle figure with a taste of literature… he will not resort to extremism… » NMU, the editor of ‘Le Cernéen’ was an avowed racist, bitterly anti-indian, virulently attacked Dr Ramgoolam and unwittingly made him emerge as the leader of the Indians and as cool responsible and reliable in the eyes of the Colonial Administration. Despite the fact that since his return to Maurtius in 1935, Dr Ramgoolam kept aloof from the Maurtius Labour Party of Anquetil and Rozemont, at best showing a guarded and cautious interest in it, he became the spokesman of Labour in the Legislature due to his proximity to the Colonial regime. And despite his aloofness until 1954/55 he became the leader of the Maurtius Labour Party (MLP) on the death of Rozemont in March 1956. He had a firm grip on the Party, his leadership was unchallenged inspite of an attempt by Raymond Rault. Dr Ramgoolam’s MLP was elitist, indianised, built from top to down unlike the Anquetil Rozemont MLP built from the bottom to top with the base the voice of Creole artisans and Indian Labourers. Il will be sheer political dishonesty to identify Dr Ramgoolam MLP with that of Anquetil and Rozemont. Yet Dr Ramgoolam unashamedly plundered these original labour pantheons for his political iconography solely for his personal success; Indeed father Seewoosagur’s and son Navin Chandra’s MLP is a proteau party with an exceptional capacity to constantly reinvent itself by repeated emphasis on the iconic image of its pantheons Anquetil, Rozemont and Seeneevassen. Dr Seewoosagur Ramgoolam’s chequered passage in Port-Louis municipal elections has been glossed over. He got himself elected as an independant candidate in 1940. In the 1943 and the 1946 municipal elections he was a candidate of the ‘Union Mauricienne’ (fore-runner of the Parti Mauricien rebaptised PMSD in 1946) and he was elected along with Jules Koeing, Raymond Hein, Maurice Poupard, Maxime de Sornay defeating Guy Rozemont, Labour and Edgar Millien independent and defeating even Renganaden Seeneerassen ! Dr Ramgoolam was a political survivor using and discarding anyone. His long-term friends Beejadhur and Vaghjee elected along with him in 1948 and 1953 were sent on political retirement when defeated. Vaghjee defeated in 1959 by (IFB) Jaypal and had to find a niche as Speaker, Beejadhur defeated by IFB Anerood Jugnauth in 1963 was made Governor of Bank of Mauritius where he faded in anonymity. Jaynarain Roy never became a Minister. Even the famous Dr Maurice Curé, founding father of MLP, never got an MLP ticket and Gaëtan Duval, Sookdeo Bissoondoyal used and pathetically discarded at will by Dr (Later Sir) Seewoosagur Ramgoolam.

SSR was a colonial collaborator and a compromiser on Chagos, yet conveying the image of ‘architect of independence’ . After March 1968, in his determination to survive he altered the character of the Maurtian State and of democratic politics. He established the filaments of patronage, floor crossing. He shifted his rhetoric from left to the right and back to the left again. He offered himself as an individual object of adulation, identification and trust – chacha. He exuded absolute political power. But it was the random sporadic power of a despot finally thrown out of power in 1982.

No wonder our Legislative Assembly had a spring clean in 1982

Let us see how SSR used constitutional electoral provisions to retain power and for the maximum benefit of his Labour Party. He draggedDuval into a coalition in 1969 and threw Sookdeo Bissoondeyal out in the Opposition after luring most IFB parliamentarians into his party. He postponed the General Election to 1976. After the humiliating defeat of his party in the 1970 bye-election at Triolet-Pamplemousses, he outlawed bye-elections. He sent best-loser Guy Balancy to the UN as Permanent Representative replacing him by Régis Chaperon, Forget to Paris embassy replacing him by Jean L’Homme. He avoided six bye-elections: Dahal died and was simply replaced by Rossenkhan, Moignac died he was replaced by d’Unienville, Gaëtan De Chazal resigned replaced by Paulo Hein, Yousouf Ramjan died replaced by Suleiman Bhayat, Gokulsing died replaced by Mrs Poonoosamy, Joomadar resigned (to take diplomatic posting in Delhi!) replaced by Balgobin. For the period 1976 to 1982 he avoided three bye-elections and made three parliamentary nominations among them his party Secretary Kher Jagatsing, replacing H. Bhugaloo who resigned and the self-appointed low caste spokesman Ghurburrun, replacing Mahess Teelock who died.

Political defection became a norm of political and parliamentary behaviour, political patronage a way of life for political sycophancy. This is the sad legacy of political culture SSR has left us. Twenty eight of the seventy parliamentarians changed party political allegiance in the period 1968 to 1976. Fifteen of these defected to join Ramgoolam’s Labour Party where most were given ministerial portfolios or parliamentary Secretary posts. In the period 1976 to 1982 eighteen parliamentarians changed party allegiance: nine of them defected from the MMM to join Ramgoolam’s Labour Party and were given the usual political patronage.

Within the honest Governing class there was, by fear or resignation, a decline of intellectual self-reflection. And intellectuals outside the Government slumped into despair and slumber or catatonia. Politics and the state, once seen as prophylactic that would invigorate the country, were now seen as a disease. No wonder our Legislative Assembly had a spring clean in 1982.

HISTORY : Independence and post-colonial Mauritius (1968-1982)

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻