“A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history”

This could well have been the synopsis of the epic Lord of the Ring but it isn’t. It is rather the words of the Mahatma Gandhi, pronounced during his non-violent pro-independence campaign in India. It is easy to theorise between closed walls and imagine a better world and feel good about oneself but it is quite another to pursue one’s dreams relentlessly in the face of adversity and criticism. To this ‘small body of determined spirits’, I would like to extend a warm thank you on behalf of all Mauritians who believe in a singular national identity. It has taken many a year to get here but the wheels of change can never be stopped. I hear that this time bond, which this expected electoral reform is, has its origins in a certain 5,000 strong protest in front of parliament in 1982. Comme quoi, the butterfly effect can be trans generational…

The Prisoners’ Dilemma and Mauritian Politics

This dilemma is aparadox in decision analysis in which two agents acting in their own best interest pursue a course of action that does not result in the ideal outcome. It is a shame and perhaps testimony to the urgent need to reform our electoral system that our political oligarchs were unable to reach a consensual agreement on an electoral reform over the last decennials. If there is to be a reform, it will have emanated from the judicial field. Had the UN Human Rights Committee not pronounced itself on this particular matter, the deadlock would not have been broken. What does this say about our political class? Errr, well, hmmmm….what about pathologically unable to take tough decisions and I’m being polite. Reforms are necessary if societies are to evolve. We should aim for an electoral system which emboldens decision-making and it is a fact that our current system is far from conducive to that given its propensity to favour bipolarization and hence the paradox of the Prisoners’ Dilemma.

Power to the people

At each legislative election, we transfer our direct democratic rights to our MPs so that they can represent our rights in parliament in what is known as representative democracy. But at each election, we regain our direct democratic right of political choice through the ‘one person-one vote’ system. If we do engage in direct democracy to elect the bearers of our future, is it not legitimate that we have recourse to direct democracy to validate the electoral system which will elect our representatives. There is here no need to ask the citizens to choose between alternative systems; a classic ‘Yes or No’ referendum based on a consensual proposal by our mainstream political parties would be welcome.

The counterproductive 10 percent threshold

If one of the aims of the electoral reform is to discourage the formation of pre-electoral unnatural alliances, then the 10% threshold is hardly the way forward. If the 10% threshold were to hold as part of the PR system, the ‘ka-da-dak’-ing of large political parties by smaller ones is unlikely to stop. It would be really ironic if the reform of the system consolidates the bipolarization of the political scene. One of the advantages of the PR system, especially the one which works under a compensatory bias, is that it promotes the emergence of new political currents – a sort of ‘democratisation of the realm of politics’. Rich democracies boast multi party parliaments. In Sweden, no less than six parties are represented in parliament while in Germany, five parties made it at the last elections held in 2013. A significant majority of countries that have adopted the PR system have set an eligibility threshold of 5 percent or less. The only country with a threshold of 10 percent is Turkey, hardly an example to follow in terms of democracy nowadays.

Where does the 10 percent come from? I have digested a fair bit of electoral papers recently and in none, including Mr Sithanen’s paper,I have found a rational explanation for the choice of ten percent. The recurrent argument is to minimize the chance of ‘extreme’ parties slipping through. So what? Isn’t a democracy meant to encourage the expression of all school of thoughts? I’d rather our electoral system recognises such extremes than try to hide them through a subterfuge. When Jean Marie Le Pen made it to the second round of the Presidential elections in France, many were shocked but none challenged the system. Instead they used the system to fight the threat which they thought the far right represented. It’s not the role of electoral systems to fight extremism but rather the role of participants within the system. We simply cannot sacrifice multi party representation and its ramifications at the expense of long lasting sequels. As such, I would propose a 5 percent threshold, high enough to prevent the ‘atomisation’ of the system and low enough to ensure multi party representation in parliament. Another way to look at the 10 percent threshold is through the prism of a conspiracy theory. Who stands to lose the most in a multi party scenario?

A system for all seasons

As architects of the future, our decision makers need to think hard about the system they want to leave behind. Do they want a quick fix or do they want a solid durable system. Since the accession to independence, less than a dozen legislative elections were held and most of them displayed a similar voting pattern. The past is rarely a good predictor of the future. Societies evolve and as such, people’s voting patterns are likely to change. So, with this in mind, I would like to stress on the importance of designing a system which will produce the desired solution under any circumstances. We cannot base our choice on the few past elections only because the voting patterns displayed in these elections are unlikely to stand the passage of time. The aim should be to leave a system that, irrespective of the voting pattern, generates the element of fairness and stability put forward by our electoral experts.

In my opinion, the First Past The Post (FPTP) system is our primary electoral system and any reform should aim to correct the anomalies of the FTPT without attempting to change its result. Thus, any party which receives more than 31 seats out of the 62 on offer should form the government. The proposed Proportional Representation (PR) should aim to reduce any disproportionality between the percentage of votes received and the number of seats obtained by eligible parties. Among one of his proposals on the electoral reform, Mr Sithanen proposes the ‘Wasted Votes’ model, also known as the ‘Unelected Vote Elect’ whereby the votes of eligible unelected candidates will be additioned to determine the number of seats each party should receive as part of a compensatory PR system. On paper, the proposal looks flawless and seems to conjugate the dual aim of stability and fairness wonderfully. Indeed, when the wasted votes method was applied to all the previous national electoral encounters, the method produced results which suggested that it addressed the problem of stability and fairness efficiently. The representation of parties was better aligned with their proportion of votes received while the government maintained a comfortable ruling majority. The dream scenario!

I beg to disagree. The ‘Wasted Votes’ model is inconsistent under the current proposals. It worked in the simulations because the voting pattern was such that it overlooked the vulnerabilities of the proposal in a Mauritian context. To recall, the wasted vote ignores the votes which goes to the elected Member of Parliament and focuses instead on the votes which went to the unelected candidate, subject to the candidate’s party meeting a predefined required threshold in terms of votes received. So the question one has got to ask oneself is whether each wasted vote has the same value. Is a wasted vote in constituency number 5 worth the same as a wasted vote in constituency number 13 for instance? Because of the wide disparity in the size of our constituencies, the answer is a straightforward NO! The biggest constituency in Mauritius (#14) is a staggering 3.4 times larger than the smallest constituency (#3).

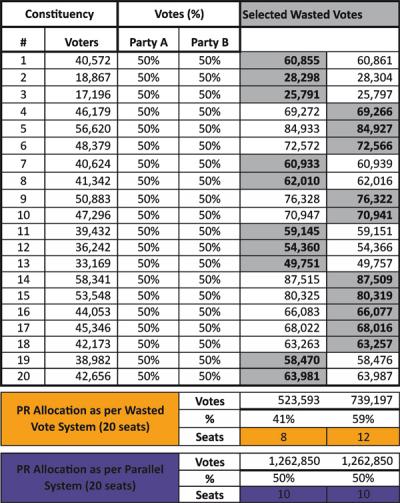

In a two-party model and assuming a turnout of 100% on polling day, if Party A was to win Constituency 14 by the odd vote (effectively 3-0), Party B would be eligible to 87,509 unelected votes. If Party B was to win Constituency 3 by the odd vote (3-0), Party A would be eligible to 25,791 unelected votes. Thus we can say that as per the Wasted Vote model, the losers in the biggest constituencies are more advantaged than the losers in the smallest constituencies. I have run a simulation of my own to highlight the unfairness of the model when constituency sizes are significantly unequal. In the simulation, I have assumed that the 3 candidates of Party A win the 10 biggest constituencies by the marginal vote (effectively 3-0) such that all the wasted votes in these constituencies go to Party B. Conversely, I have assumed that the 3 candidates of Party B win all the 10 smallest constituencies (3-0) by the marginal vote such that all the wasted votes in these constituencies go to Party A. Without going any further and based on the above, I would expect Party B to be advantaged under the Wasted Method model. The results are shown below:

We can see clearly the unfair advantage gained by Party B since they collect 59% of the wasted votes and are thus allocated 12 seats at the expense of Party A and are thus in a position to form a government. How unfair is that? According to the FPTP model, the result is 30-30 and if one were to include a parallel PR system, the 20 PR seats would be equally distributed between A and B such that the ultimate result would be a hung parliament of 40-40. Given the closeness of the results, a hung parliament is the fair result. But the Wasted Vote model gives rise to a result favouring Party B (42-38). Unless we redefine our boundaries such that all constituencies are similar in size, this model is inapplicable in Mauritius in its current proposed format. Another alternative would be to standardize the wasted votes such that each wasted vote has the same weight…Getting too complicated? I concur.

The model that we need is a simple model – easy to understand by all while achieving the dual objective of stability and improved fairness. I would favour the option whereby there is a compensatory PR system with a constraint to ensure a stable ruling majority. For example we could propose a model whereby a compensatory PR would rebalance any under representation subject to a clear majority of 3 MPs prevailing, assuming the difference between the numbers of elected members was at least 6 (3 MPs*2) at the FPTP level. Under this proposal and assuming the two-party model still holds, if Party A received 51% percent of the votes (40 elected members) and Party B received 49% of the votes (20 elected members), a compensatory PR of 20 additional members would allocate 19 seats to Party B and 1 seat to Party A such that the final result would be Party A – 41 seats and Party B – 39 seats. This is however too close to guarantee a stable government (majority of 1 MP). That’s where the clear majority of 3 MPs constraint kicks in – Party A would then be eligible for 43 seats and Party B would obtain 37 seats (difference of at least 6). Both the fairness and stability criteria are met. However, if after the FPTP, the difference is less than 3 seats (say 28-34) between the two Parties, the PR should not be able to increase that difference to 3 seats nor should it aim to reduce it. The final outcome would be a 10-10 split of the PR seats. As mentioned above, the FPTP is the dominating system and the PR should only be used as a corrective mechanism.

The King is Dead, Long Live the King

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻