Living in the United States, I don’t get too many opportunities to visit Africa, but during these past two weeks I had the chance to observe life in Kenya, Johannesburg and the tiny Kingdom of Lesotho.

From the outside looking in over a period of two weeks, and with a set of eyes jaded by modern conveniences, easy transport, diversity of restaurants and a highly open political culture, I got a taste of modern Africa.

A few quick impressions: poverty reigns in most areas, the Chinese have arrived, the Africans are super friendly and curious, and, despite concerns about political instability, corruption and global recession, economies are functioning, trading and producing services for their people.

In Kenya, I had been warned about the dangers of Nairobi. Don’t go out at night. Don’t carry valuables. Leave your wedding rings at home. There was also an active terrorism alert.

I was so alarmed that I convinced my husband to skip the downtown hotel and stay at the home of a colleague in a leafy area of the city that was protected with strong security – the same neighborhood as the US Embassy, the United Nations mission and of wealthy residents who built huge homes with lush gardens hidden behind expensive security gates.

One gem of Nairobi is the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, where we watched an amusing feeding of orphaned baby elephants as they slurped milk, kicked soccer balls and rolled in the mud. The trust takes in elephants who have been separated from their mothers (many of whom have been killed by poachers). The keepers rear them with socialization, affection and nutrition, and then release them back into the wild – a process that can take three years.

The Naivasha Valley, a two-hour drive from Nairobi, was a different world of dusty savannahs with roaming herds of zebra, giraffes, warthogs and impalas. The villages were dirt-road collections of tin houses held down with tires or rocks. Merchants on the side of the road hawked zebra skins and tomatoes.

A game drive through Lake Nakuru didn’t disappoint, with flocks of flamingoes and pelicans lining the lake, and a mountain bike trek through Hell’s Gate National Park was strenuous but rewarded by close views of giraffes and zebras and a harrowing descent by foot into the park’s magnificent gorges (where part of the movie « Lara Croft, Tomb Raider with Angelia Jolie was filmed.) Our guide there was Austin, a Masai warrior wearing a Fred Perry T-shirt, who shared the story of how he killed a lion as part of his initiation into adulthood, a requirement among the Masai people.

Beyond the splendor of these places, I got the sense that Kenya has survived the worst of the global recession, thanks largely to the presence of foreign organizations (the UN has a big presence here), exporting textiles (they are a beneficiary country under the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act), promoting tourism and trying to avoid – until recently – involvement in Somalia that might anger home-ground Islamic terrorism groups.

They also seem to have embraced and encouraged the arrival of Chinese investment, as China has now overtaken the United States as the single largest trading partner in Africa. In fact a recent article in the Daily Nation, Kenya’s largest newspaper, suggested that the Chinese treat the Africans with more respect than Americans do, and show a much stronger, sustained interest in investment and trade.

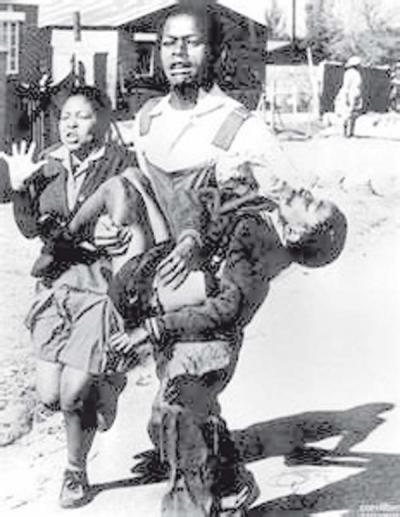

In Johannesburg, I had the chance to revisit the history of apartheid, something I had witnessed from afar in the 1970s through TV reports of events like Mandela’s arrest and the Sharpeville massacre. I also participated in protests at my American university to object to the school’s investments in U.S. firms doing business in apartheid South Africa. This all came alive again with a visit to the Apartheid Museum in central Joburg, and a drive through Soweto, site of the violent student uprising that launched the national resistance movement in 1976.

I learned several new things: that the Afrikaans language is more than a Dutch dialect. It is a mix of German, French, Portuguese, Malay and African languages, and is no longer the official language, but one of 11 spoken in South Africa; that it costs $5 million to buy a home in the tony Houghton district of Joburg, where Nelson Mandela and Bishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu now have homes; that Gandhi practiced his ethos of non-violent protest in defending the rights of Indians when he lived in South Africa for 21 years from 1893-1914; that, among other business ventures, the Chinese have cornered the blanket market, knowing that blankets are an important purchase among Black South Africans; that Soweto, short for South Western Township, and created essentially as a black ghetto, was a vibrant center for poetry and the arts through the 1970s, and that today the rebuilt town is a popular tourist destination and has a 2 percent white population; and that « pass laws » became the most powerful tool of apartheid as they restricted movement of Blacks outside their homelands, with the threat of arrest and prison for those not carrying their passbooks.

Nearly 18 years since the end of apartheid, South Africa’s transition is still a work in progress. A new constitution has paved the way for more integration, better education and broader economic opportunities and advancement for those once denied them. But while I was there, there still seemed gaps in the dream created by Mandela and Bishop Tutu of a rainbow nation.

Writing in the Johannesburg Sun last Sunday, Luzuko Jacobs, spokesman for the South African Parliament, questioned whether the country was ready and willing to accept cultural differences in a post-apartheid society.

He recounted how on the first day of school, his 11-year-old son was told by administrators at his integrated school near Cape Town that it was « inappropriate » for him to wear an « intambo imbeleko, » a traditional necklace made with animal hairs that is worn by Zulus and Xhosa.

« Why are Black students expected to assume « acceptable identities » in the name of integration? » he asked.

In another article in the Sun, journalists criticized new efforts by the SA government to restrict press freedoms.

Moving on to Lesotho – about an hour away by plane – we found ourselves in this tiny, mountainous country that is run by a monarch, King Letsie III.

Located smack in the middle of South Africa, this landlocked country was created for the Basotho people in the mid-1800s and became independent in 1966. The capital, Maseru, is 5,000 feel above sea level, and is a haphazard collection of decrepit 1960s-era buildings and honking cars. It is the starting point for mountain hikes in the summer and skiing in the winter, as mountains are blanketed in snow in June and July.

The country is heavily dependent on South Africa for its economy, yet has developed its own textile industry – largely from trade with the U.S. under AGOA – and it mines diamonds and supplies water to the city of Johannesburg. People also make modest livings in agriculture, as many villages are in remote highland areas that are only accessible by foot or horse.

The grip of poverty is evident everywhere, as people line up for rides in old taxis and buses, women wear traditional dress and strap babies to their backs, and many live in inadequate brick houses or aluminum shacks without running water and with a roof attached with tires or rocks. Yet there are signs of progress, especially in the health sector.

I visited two new medical facilities that offer up-to-date equipment and dedicated and well-trained staffs. They are among the most advanced in Africa, and are helping Lesotho address the high rate of TB, HIV-AIDS and maternal mortality that have come to define life in this country.

The Queen Mamohato Memorial Hospital, opened last October, was financed by the IFC and the World Bank, and is managed by a South African company. I accompanied my husband, Jean-Jacques, and his team from the World Bank, on a visit to observe hospital operations.

Doctors are an international crowd, coming from Cuba, the Republic of Congo, India, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, as medical students from Lesotho who study in South Africa tend not to return home. We visited the maternity ward where girls in their mid-teens tended their babies, and infants born prematurely – one weighing just one pound – struggled for life with the aid of modern machines.

The second facility was a filter clinic where people go for primary care. It is located in a remote village, accessed by dirt roads and surrounded by a barbed wire fence and the poverty of village life. The contrast between the modern facility and the primitive living conditions is striking.

The waiting room was filled with the old, the young, crying babies. In treating sick patients, doctors have the added challenge of competing with traditional medicine in the village. Setting up links to the local community is essential, Dr. TG Prithiviraz, the very energetic and optimistic clinic manager from Sri Lanka told us. Now we leave Lesotho and the African soil for Mauritius. I’m looking forward to observing how the country has grown and changed since I last visited more than two years ago.

A LETTER FROM AFRICA: Looking at the continent with western eyes

- Publicité -

EN CONTINU ↻

- Publicité -